This instrument was restored in 1981-1983 by someone who called himself "Pud." His signature was found under the replacement pedals he made. On the underside of the other pedal he proclaimed that he loved "Beenie." Ok. I don't want to know who Pud is or was, but this bit of trivia tells me one thing--that the instrument has been in the US since at least 1981, probably earlier. Most recently it came out of a storage unit owned by a collector who died before he was able to restore it.

Pud did a number of things that were more common in the 1970's when reed organ restorers were following the teachings of Horton Presley, who advocated for the use of modern synthetic materials. "Space Age" materials, I call them. Contact cement, PVA white glue, neoprene, genuine imitation leather, the whole shebang. I grew up in the 60's when traditional methods of repairing things were going by the wayside, and collectively we were brainwashed to think that modern, synthetic glues and materials were superior to traditional, organic materials. "Just like the astronauts use!" was a line we willingly absorbed. In retrospect, the astronauts didn't have anything in their space ships that were made of wood and leather, so hide glue was out of the question.

When using space age materials what Pud didn't take into account was what the marvelous synthetic glues would look like after 40+ years. It isn't a pretty sight. Synthetic material often does not age well. Glues touted as flexible even after application turn to concrete that may come up with a chisel if you're lucky, although it often will bring some of the wood it's attached to with it.

This first "restoration" of this harmonium is a case study in geriatric synthetics. One example is the neoprene that he used to replace the wadding. Although traditional wadding springs back when the action is opened, it will eventually settle into a pattern that conforms to the wood that is pressed into it. However, wadding can last a century or more. Pud's neoprene did not. These pictures tell the story on that.

Although the neoprene did conform to the underside of the edge of the reed chest it deteriorated with time. Old neoprene will often crumble when handled, as this did (see below). It didn't come up in one long strip. The white glue that held it down also caused it to come up in short pieces.

Below is another example of space age materials used to solve a problem. The white material to the left side of the reed chest was initially a mystery to me. It wasn't paint, and it had texture. It was slathered over seemingly random spots on the chest. Then the light bulb went on. When I started to scrape it off I realized it was joint compound. Yep, that's right. Mud for sheet rock. Pud used this to attempt to seal insect holes and cracks.

These were the most obvious uses of synthetic materials that seemed to be better but in fact were much, much worse. I've seen other examples over the years. Contact cement to hold down bellows cloth that had turned to concrete and had to be cut off with a table saw, things of that nature.

I hope this gives you a general idea of what NOT to do when restoring an antique musical instrument. The best thing to do, as much as possible, is to do what the original builder did. As much as possible use natural materials such as wool and leather. Hide glue, either hot or cold liquid.

As a general rule, adhesives that come in a tube and have warnings about the brain damage that will occur if you sniff them are synthetic. Run away in the other direction.

Disclaimer: in a future post I will describe how I made new wadding for the harmonium. I used yarn made of 80% wool and 20% nylon. The cautions above are mostly for synthetic glues and foam materials. Fabric can be a different matter depending on how it's used. Where leather is needed, don't use anything except real leather. Bellows cloth, traditionally made from canvas coated on one side with rubber, has become exorbitantly expensive, and restorers often to go synthetic materials not originally made for that purpose. You want to be sure that the material will work with hide glue. Polyester is a great material but it doesn't do well with hide glue. For felt and woven cloth, use 100% wool felt or cloth as much as possible. Pure wool springs back. Synthetic felt will often not. For the yarn I mention above that I used for wadding, 20% nylon isn't enough to prevent the wadding from springing back when the action is opened.

The reason for all this is twofold:

1) Once restored, it may be at least 50 years before your instrument is restored, if it is still in existence. Materials that don't age well won't work as well half a century later. This is especially true of synthetic glues, which are very difficult to deal with in their dotage. Some elements of case work and other parts of the organ are ok with yellow carpenter's glue, for instance. I used it in specific places in this instrument where nobody would want to have to take it apart and do it over.

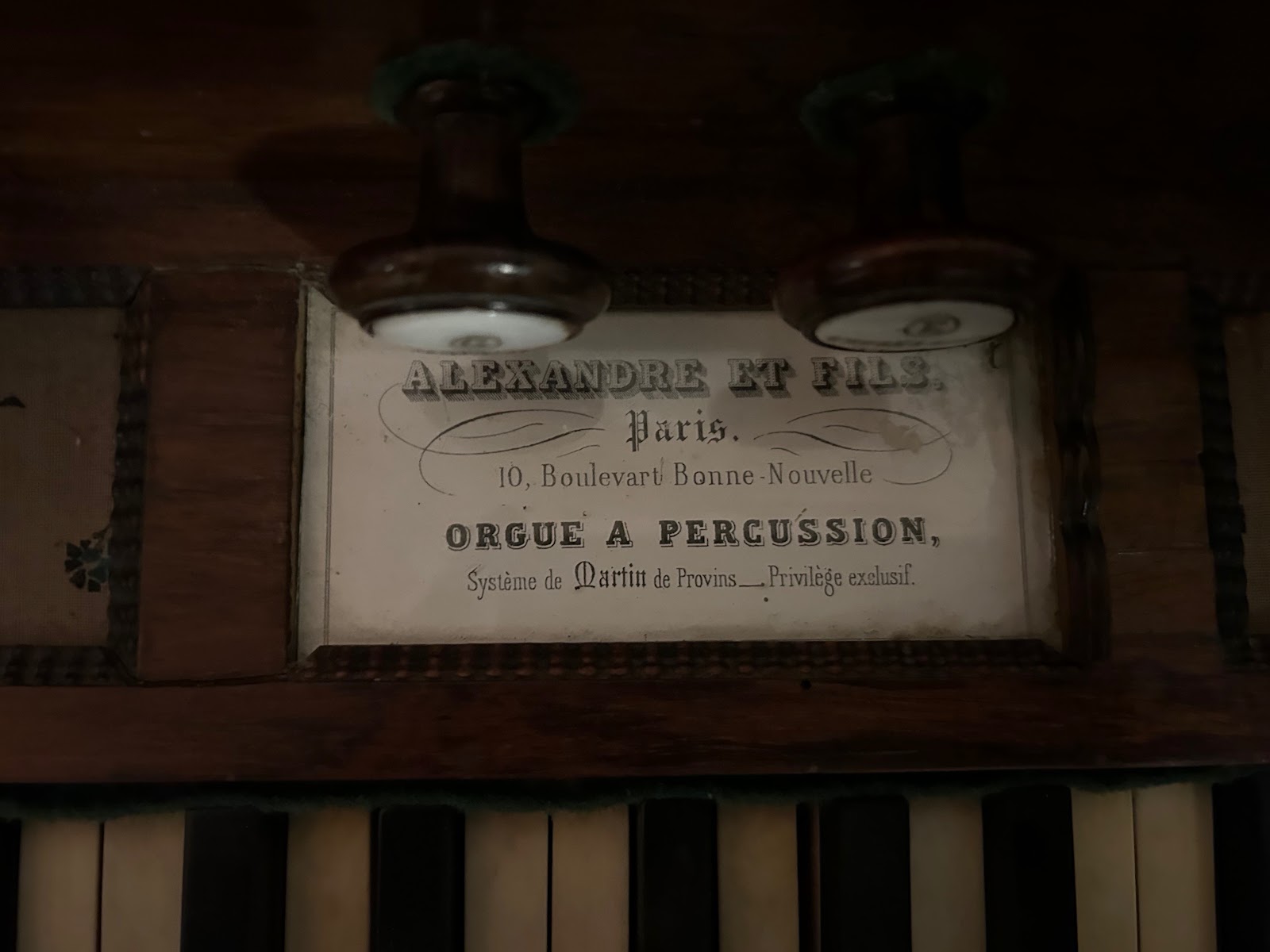

2) When you're restoring an instrument, you have to undo the work of the builder or the person who worked on it before you. In the case of my harmonium, the previous restorer did a hack job. No tears were shed by me as I scraped and sanded the neoprene off the valve board. But here's the thing. Keep in mind that if the organ you are restoring is still in existence 50-75+ years from now, someone is going to have to undo what you've done. Let that sink in. Someone is going to have to undo what you've done. If you use synthetic adhesives and other such stuff they will have to go through what I have with this instrument, and they will not thank you. Some restorers have looked at an instrument restored with synthetic adhesives and have decided it was not worth redoing the organ, and it went to the landfill. You don't want that to happen. I have continued with this instrument despite Pud's amateurish restoration because it is very old and very rare. It's been worth the trouble despite the occasional headache (not caused by sniffing 40 year old glue).

More next time!